What Is IBS?

With an ever-evolving list of symptoms and possible causes, the gastrointestinal disorder known as Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is generally defined as:

A widespread, chronic gastrointestinal condition involving recurrent abdominal pain and diarrhea or constipation, often associated with varying instigators, including stress, depression, anxiety, or previous intestinal infection.

Statistical data from the nonprofit International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders, reveals approximately one in every 10 people is afflicted with irritable bowel syndrome, making IBS the most common functional GI disorder. So, if you think you may be dealing with IBS, rest assured that you are not alone, and that there are processes in place to diagnose and treat your symptoms.

"With IBS, the colon is overly sensitive to the natural contractions that move food through the intestines, causing pain, bloating and strong urges for a bowel movement."

What’s a Functional GI Disorder?

Functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) are health conditions that cause the functionality of your gut to be thrown off, but are not necessarily precluded by any discernible underlying pathophysiological causes. What that means is that functional GI disorders won’t cause physical damage to your gut, i.e. ulcers, inflammation, thickening of tissues or abnormal blood test results. If any of the aforementioned were to occur, that might indicate a different sort of condition altogether. Instead, with IBS, the colon is overly sensitive to the natural contractions that move food through the intestines, causing pain, bloating and pain with for a bowel movement.

According what’s known as the ‘Rome Diagnostic Criteria’—internationally accepted characteristics to help identify and treat functional gastrointestinal disorders established by North Carolina-based nonprofit The Rome Foundation—there are currently 24 different FGIDs classified within six subcategories:

| Subcategory | Example |

| Esophageal | Functional Heartburn |

| Gastroduodenal | Belching Disorders |

| Bowel | Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) |

| Biliary | Functional Gallbladder Disorder |

| Anorectal | Fecal Incontinence |

| Abdominal Pain | Centrally Mediated Abdominal Pain Syndrome (CAPS) |

Worldwide, it is estimated that FGIDs affect about 20% of the population.

The Rome IV Diagnostic Criteria for IBS

The Rome process and criteria are parts of an international effort to continuously build upon scientific data to help in developing more accurate processes for the diagnosis and treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders, such as those mentioned in the table above.

The Rome criteria are ever-evolving; for instance, there are several glaring differences between the Rome III criteria and the Rome IV criteria, even with just a decade separating the two publications.

| What’s Different? | Rome III (2006) | Rome IV (2016) |

| Defining FGIDs | Defined, simply, by “an absence of structural disease” | Newly defined as follows:

“Disorders of gut–brain interaction.” FGIDs are a group of disorders classified by GI symptoms related to trouble with any combination of the following:

|

| Frequency Over Time (IBS) | Recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort at least three days/month in the last three months associated with two or more of the following: | Recurrent abdominal pain, on average, at least one day/week in the last three months, associated with two or more of the following criteria: |

| Accuracy (IBS) |

|

|

| Clarity (IBS) | “Discomfort” means an uncomfortable sensation not described as pain. | Pain is still an essential part of the diagnosis, but the word “discomfort” has been removed. The authors believed that “discomfort” was vague and unclear. Another challenge is that not all languages have a word that means “discomfort,” which makes translation difficult. |

The time requirements are used to differentiate IBS from common stomach issues that everyone struggles with from time to time.

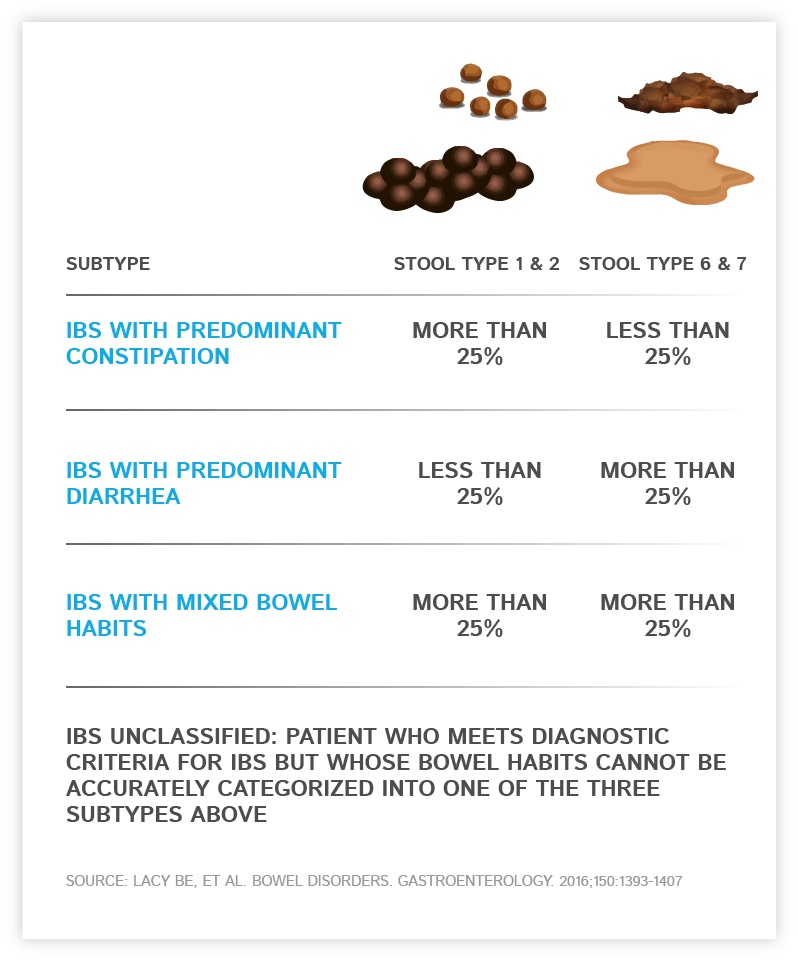

IBS Subtypes

There are four IBS subtypes a patient may be diagnosed with. It’s important for patients to know their subtypes, as it may affect their dietary choices.

- IBS-C: IBS With Predominant Constipation

- IBS-D: IBS With Predominant Diarrhea

- IBS-M: IBS With Mixed Bowel Habits

- IBS, Unsubtyped

Below are two educational charts outlining stool consistency and frequency that may be cross-referenced to determine a patient’s IBS subtype (IBS Subtypes Chart: IrritableBowlSyndrome.net):

Symptoms of IBS

Patients with IBS may suffer from a broad range of symptoms.

Be sure to bring your concerns to the attention of your doctor if you are experiencing any combination of the following symptoms associated with IBS:

- Abdominal Pain

- Nausea

- Cramping

- Persistent Bloating

- Diarrhea

- Constipation

Although IBS is affiliated with the bowel, some of these symptoms originate in the upper portion of the gut, i.e. the esophagus and stomach.

Other symptoms can include gas, incomplete bowel movements, defecation of mucus into the toilet, loud gut rumblings, and pain in the rectum.

IBS Causes and Triggers

IBS is an FGID, and so by definition, does not have any known cause, making it appear more elusive than other, more predictable diseases. However, there are some factors that seem to present consistently enough among IBS patients to imply some correlation between them and IBS.

Here are some facts about the origins of the most common IBS symptoms and symptom triggers, to help dispel the air of mystery encompassing the medical head-scratcher that is IBS:

Layers of muscle contract within the walls of the intestine to propel food and waste through your GI tract. Some IBS patients experience contractions that are stronger and longer-lasting than normal. In this case, the patient would likely experience gas, bloating and diarrhea. On the other hand, some IBS patients experience weaker intestinal contractions than normal. (This contributes to the motility disturbance requisite in the Rome diagnostic criteria for FGIDs.)

Many patients become afflicted with ongoing IBS only after first developing severe gastroenteritis (diarrhea) caused by bacterial infection or a virus. This is called postinfectious IBS, and people who suffer from it may have persistent, albeit very mild, inflammation of the gut. Unfortunately, anti-inflammatory drugs seem ineffective as treatment options.

Additionally, the microflora, or “good” bacteria living in your intestines, have a large say in your overall quality of health. Some research points to an imbalance in microflora in IBS patients when compared with that of healthy people’s guts. This is called dysbiosis, and there are different theories about how and why it affects the bowel, such as:

- Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO)

- Food-Related Causes: The things we eat influence the production rates of different types of bacteria in our bowel. Research is being conducted to determine whether these bacterial changes might cause IBS symptoms by actually changing how the Enteric Nervous System (ENS)—neurons controlling gastrointestinal tract function—interacts with your bowel.

- Early Childhood Exposure: Every gut is different; our unique set of bacterial types in our bowel begin forming during childhood. It’s possible that environmental factors other than the food we eat may also contribute to the way our ENS is “tuned.” (This contributes to the altered mucosal and immune function and altered gut microbiata requisites in the Rome diagnostic criteria.)

Twin studies and other genetics research seems to allude to the probable connection between IBS and familial heredity. However, the connection is not considered to be “Mendelian,” wherein the likelihoods of inheritance are easily predictable. Even though IBS tends to aggregate within families, the lack of clarity regarding the source of these genetic ties implicates IBS as a “complex genetic disease.”

There is a great and powerful connection between your brain and your gut. In fact, more neurons are thought to inhabit the human gut than the entire spinal cord. Activity in your gut is mainly managed by the visceral motor system. The visceral motor system, however, does not seem to govern the extensive plexus of neurons living within the walls of the intestines and accessory organs, such as the pancreas and gallbladder. These nerves make up what’s known as the Enteric Nervous System (ENS), which regulates several systems of the GI tract to form functionally effective patterns of certain digestive states.

The links between the brain and ENS are collectively referred to as the Brain-Gut Axis; disturbances contribute to IBS symptoms. (Recall the Rome diagnostic criteria, altered central nervous system processing.)

Nerve Misfires

If there are abnormal nerve responses persisting in your digestive system, they could be causing intensified discomfort when your gut stretches from gas or waste. This can affect the ENS by altering how the nerve signals from the gut are communicated to and interpreted by the brain and spinal cord. (See: Rome IV diagnostic criteria, visceral sensitivity.)

Stress

Evidence strongly suggests that IBS is a stress-sensitive disorder. For instance, psychological disorders such as depression and anxiety present more often in patients with IBS when compared with healthy psychological controls, and is most prominent in patients with the IBS-C subtype. A possible explanation for this can be found in the excerpt below.

Serotonin

5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), otherwise known as serotonin, is an important chemical and neurotransmitter with essential roles in maintaining GI motility, visceral sensitivity, GI immune function, and blood flow. Serotonin is also commonly understood to influence relative levels of happiness. In the GI tract, serotonin is released as a neurotransmitter by the ENS to aid intestinal motility and secretion by increasing the firing rate of certain neurons.

The IBS subtype IBS-D (predominant diarrhea) typically shows increased serotonin production leading to rapid GI motility and increased blood flow, which contributes to IBS-related diarrhea.

The opposite occurs in patients with IBS-C (predominant constipation). With IBS-C, there is an increased concentration of serotonin in the innermost membrane of the colon (colonic mucosa) when compared with IBS-D patients, suggesting impaired release of serotonin.

Food Intolerance

IBS symptoms are sometimes triggered by a food intolerance. This is good news: It means there’s hope yet to make dietary changes that could drastically reduce the severity of your IBS-related discomfort.

Here is a list of some of the most-frequently IBS-triggering foods:

- Fiber: Soluble fiber and insoluble fiber affect digestion differently. Soluble fiber attracts water and slows down digestive motility. On the other hand, insoluble fiber works to speed up motility. Which kind of fiber to avoid and which to seek out will depend upon a patient’s IBS subtype.

- FODMAPs: FODMAP stands for Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides and Polyols. If these terms are unfamiliar, remember that saccharide is simply another word for sugar. In short, FODMAPs are carbohydrates that are readily fermented by bacteria.

Below is a list of high-FODMAP foods to avoid if you suffer from IBS:

Vegetables

- Onions

- Garlic

- Cabbage

- Broccoli

- Cauliflower

- Snow peas

- Asparagus

- Artichokes

- Leeks

- Beetroot

- Celery

- Sweet corn

- Brussels sprouts

- Mushrooms

Gluten

- Wheat and rye

- Breads

- Cereals

- Pastas

- Crackers

- Pizza

Learn more about Gluten Sensitivity

Fruits

- Peaches

- Apricots

- Nectarines

- Plums

- Prunes

- Mangoes

- Apples

- Pears

- Watermelon

- Cherries

- Blackberries

- Dried fruits

Dairy Products Containing Lactose

- Milk

- Cheese

- Yogurt

- Ice cream

- Custard

- Pudding

Nuts and Legumes

Sweeteners and Artificial Sweeteners

- High fructose corn syrup

- Honey

- Agave nectar

- Sorbitol

- Xylitol

- Maltitol

- Mannitol

- Isomalt (commonly found in sugar-free gum and mints, and even cough syrups)

Drinks

- Alcohol

- Sports drinks

- Coconut water